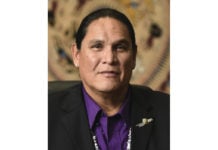

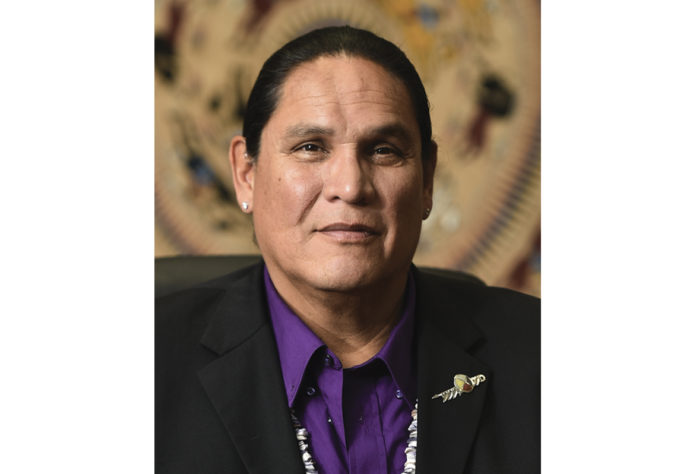

by Ernest L. Stevens, Jr.

As we continue to recover from the damage the COVID-19 pandemic has caused to Indian Country, we have yet another reminder that the fight continues to defend our industry and the sovereignty of Native Nations. Recently, we have seen an uptick in attacks on federal laws that affirm the U.S. Constitution’s recognition of Indian tribes as governments and are designed to meet the federal government’s solemn treaty and trust obligations. This effort, led by anti-tribal sovereignty organizations, urges courts to strike down laws that respect the governmental status of Indian tribes, and in turn, argues to that Indian tribes be classified as race-based.

Building on this growing trend, a commercial cardroom operator in the State of Washington recently filed a lawsuit against the U.S. and the state, claiming that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) and compacts between Washington State and tribal governments are unconstitutionally based on “race and ancestry.”

These attempts to nullify the political status of tribal governments ignore well-settled federal Indian law and the express language of the U.S. Constitution.

It is an undisputed fact that Native Nations pre-date the formation of the U.S. Indian tribes were independent, self-governing entities vested with full authority and control over their lands, citizens, and visitors to their territories. Upon contact, the nations of England, France, and Spain all acknowledged Indian tribes as sovereigns and entered into treaties to establish commerce and trade agreements, form alliances, and preserve the peace.

Upon its formation, the U.S. acknowledged the sovereign authority of Indian tribes, entering into hundreds of treaties with tribal governments. The U.S. Constitution specifically acknowledges these treaties and the status of Indian tribes as distinct governments. The Commerce Clause provides that “Congress shall have power to … regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.” This clear text establishes the framework for the federal government-to-government relationship with Indian tribes.

These basic tenets have grounded and guided the evolution of federal Indian law and policy over the past two plus centuries. In the COVID-relief packages enacted to address the health and economic impacts of the pandemic, Congress included historic levels of direct spending to tribal, state, local, and territorial governments. These provisions further engrain the governmental status of Indian tribes as separate distinct sovereigns within our constitutional system.

The commercial cardroom’s challenges to the Washington-tribal government compacts are also not new. Other courts have rejected similar challenges, holding that “The very nature of a tribal-state compact is political; it is an agreement between an Indian tribe, as one sovereign, and a state, as another.”

Reviewing courts also reasoned that Congress, as it debated the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, recognized that tribal governments had been engaged in gaming on Indian lands to generate governmental revenue long before the Supreme Court’s 1987 Cabazon decision. Congress, through IGRA, established the tribal-state compacting process to balance competing interests of the tribes and the states, which it acknowledged as “two equal sovereigns.”

While not grounded in law or fact, we take these challenges seriously, because of what is at stake. For most of the past half century, more than 200 tribal governments nationwide have utilized Indian gaming to generate governmental revenue to rebuild our communities.

Our industry, before the COVID-19 pandemic, generated more than 300,000 direct jobs and over 700,000 jobs indirectly Indian lands annually, making Indian gaming collectively the 11th largest private employer in the nation. Tribal government-run gaming operations serve as economic anchors for community development and entrepreneurship.

IGRA mandates that revenue generated by Indian gaming operations be used for governmental purposes, a function tribes have practiced long before IGRA was passed. For more than 34 years now, Indian gaming revenues have been used to put a new face on Native communities – rebuilding basic infrastructure, and enhancing the delivery of health, education, and public safety services to their citizens.

These legal challenges that attempt to blur the distinction between Native Americans as a race of people, as opposed to the political nature citizens of constitutionally recognized tribal governments, attack the very core of tribal sovereignty.

As Justice Blackmun wrote in the historic Mancari decision in 1974, if these legal challenges are upheld, “an entire Title of the United States Code would be effectively erased and the solemn commitment of the government toward the Indians would be jeopardized.”

The National Indian Gaming Association stands united with our Member Tribes and the Washington Indian Gaming Association in denouncing the Maverick Gaming lawsuit as dangerous, destructive, and lacking any merit. We will continue to fiercely oppose any attempt to undermine the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and the very foundation of federal Indian law and policy.

Ernest L. Stevens, Jr. is Chairman of the National Indian Gaming Association. He can be reached by calling (202) 546-7711 or visit www.indiangaming.org.