by James M. Klas

The past two years have brought challenges to the Indian gaming industry that surpass anything it has faced since its initial struggle for recognition and legitimacy. Tribes and casino managers across the country have performed admirably under unprecedented circumstances for an industry less than 40 years old. But as the pandemic fades, at least as a direct economic threat, it is not the lingering possibility of renewed outbreaks that holds recovery back, not the possibility of new mandates or restrictions, not even the sudden jump in operating costs from inflationary pressures. The single biggest impediment to full recovery and renewed growth is the lack of available labor to allow casino resorts to operate at full capacity. Even in markets where revenue and profits are surpassing pre-COVID levels, labor availability is holding back further growth.

There is little question that the upheavals of the pandemic and associated mitigation efforts played an important role in spawning the current labor crisis. Many employees were lost to extended closures that caused a reevaluation of career and even lifestyle choices. Government support, much needed to cushion the blow and sustain the economy, gave people more room to consider and then pursue new paths. When the pandemic restrictions were lifted with COVID deaths declining, customers started to return to Indian casinos, but employees did not, at least not in sufficient numbers. That Indian gaming is not alone in this crisis is of little comfort. It simply means that there are even more prospective employers competing for the same tight labor pool.

Although the effects of the pandemic are pronounced, the genesis of the labor problems actually predate COVID-19. Declining labor force participation, reductions in the availability of foreign labor, under utilization of some labor force segments and lack of competitive wage rates all preexist the pandemic, even if the pandemic made them worse.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics there are now nearly two jobs available for every one person seeking a new job nationwide. More jobs than potential employees actually first appeared in April of 2018 and only the height of the early pandemic closures reversed the trend temporarily. But by May of last year, it was back with a vengeance and has steadily gotten worse. Labor force participation has fallen by four percentage points since 2002, costing the country approximately 10.4 million potential workers.

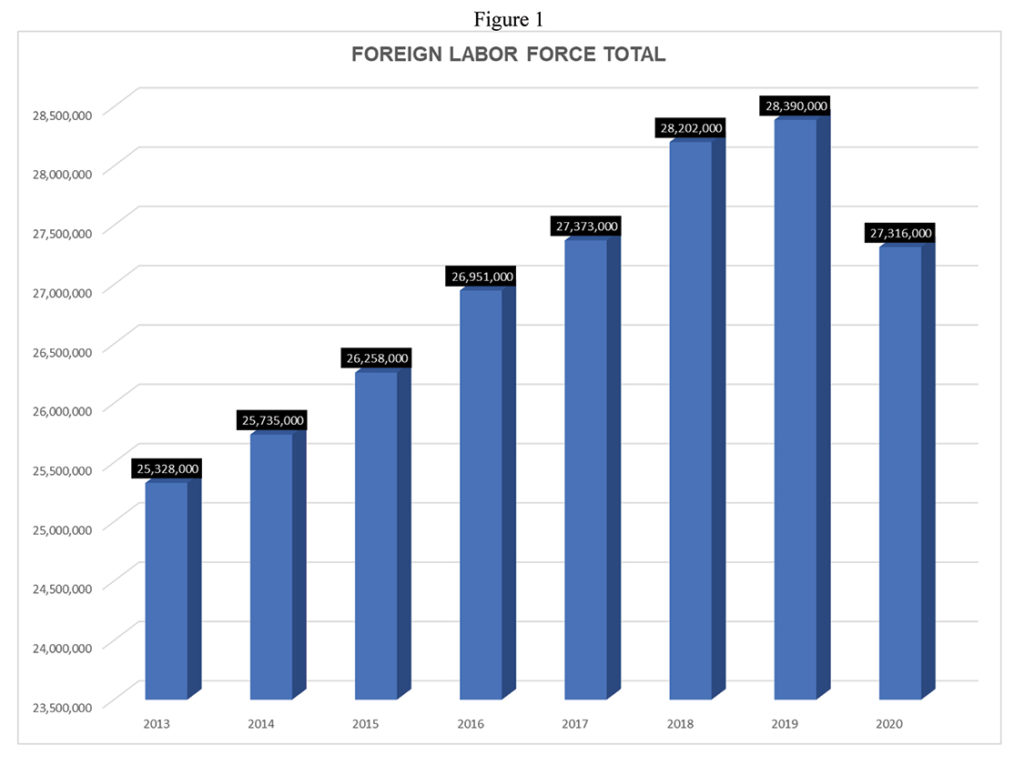

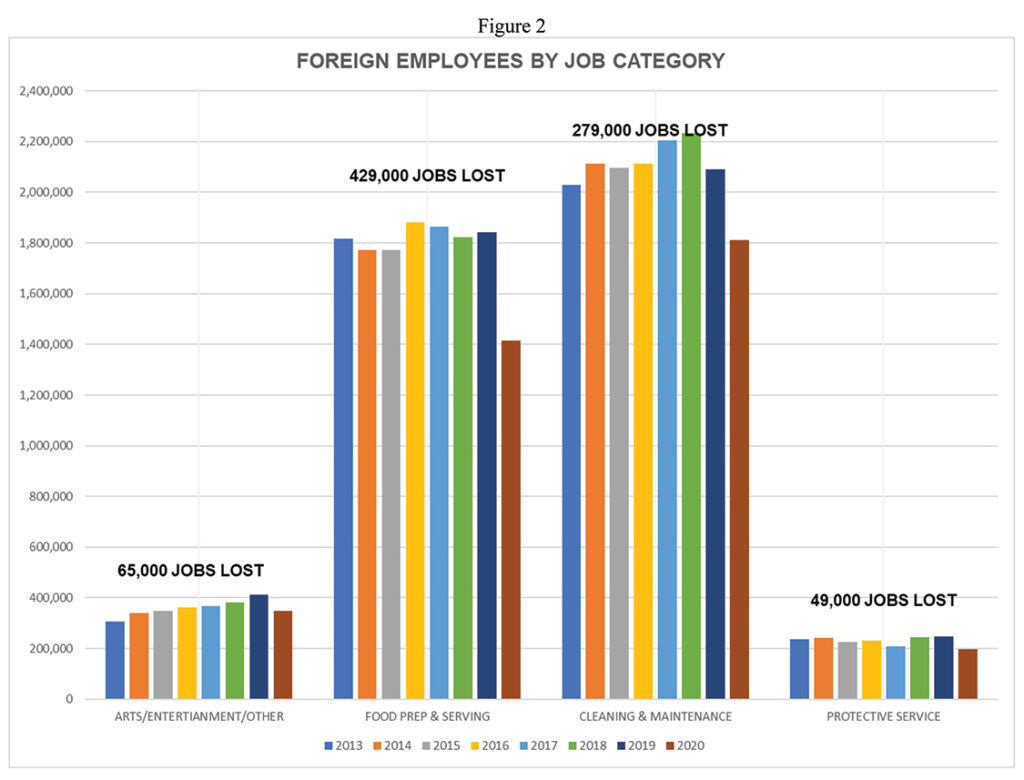

At the same time, COVID-19 restrictions and other changes in immigration policies resulted in the loss of over one million foreign-born workers from 2019 to 2020. Figure 1 shows the number of foreign workers in the U.S. from 2013 through 2020. Foreign workers are particularly critical to rural resorts and their surrounding economies. They also figure highly in food service labor pools. Nearly 46 percent of foreign workers lost in 2020 came from the food service and arts and entertainment sectors as shown in Figure 2.

The problem is particularly acute in Indian Country. According to a 2017 study by the Federal Reserve, the tourism sector accounts for over 35 percent of jobs on reservations. Tourism jobs have average wages 28-38 percent lower than the overall average wage in the U.S., putting them and tribes at a competitive disadvantage in the labor marketplace.

To address the labor crisis, casino managers are focusing on three broad strategies: retain existing employees, acquire new employees and reduce labor needs. Several steps can be taken to retain existing employees. Increased wages are obvious and actually one of the driving factors behind the inflationary pressures we now face. Beyond increased wages, however, is the need to enhance and publicize benefits like vacation and PTO, health insurance, meals and uniforms, training and educational support, and opportunities for promotion. More challenging than increasing wages and benefits, offering greater flexibility in scheduling will help combat one of the main lifestyle detriments, with pay differentials to recognize/reward less popular shifts.

Less obvious but as important is the broader work environment. Back of house areas are traditionally undersized and under-designed, making the jobs less attractive. More than just improved locker rooms, breakrooms and employee meals are needed. Storage space, distance from storage areas to actual usage, work space, lighting, employee parking and ingress/egress and other physical facility factors can affect job satisfaction. Beyond physical and policy limitations, fostering a greater sense of collaboration and teamwork between management and staff can go a long way toward increasing employee loyalty.

Many of the same things that help with employee retention help in attracting new employees as well. Pay, benefits, scheduling flexibility, training and education, opportunities for promotion and a collaborative environment can significantly increase the potential to capture new employees in a competitive labor market, provided, of course, that those strengths are well publicized. Cross-training and utilization can also fill short-term holes and increase variety and satisfaction in the work environment.

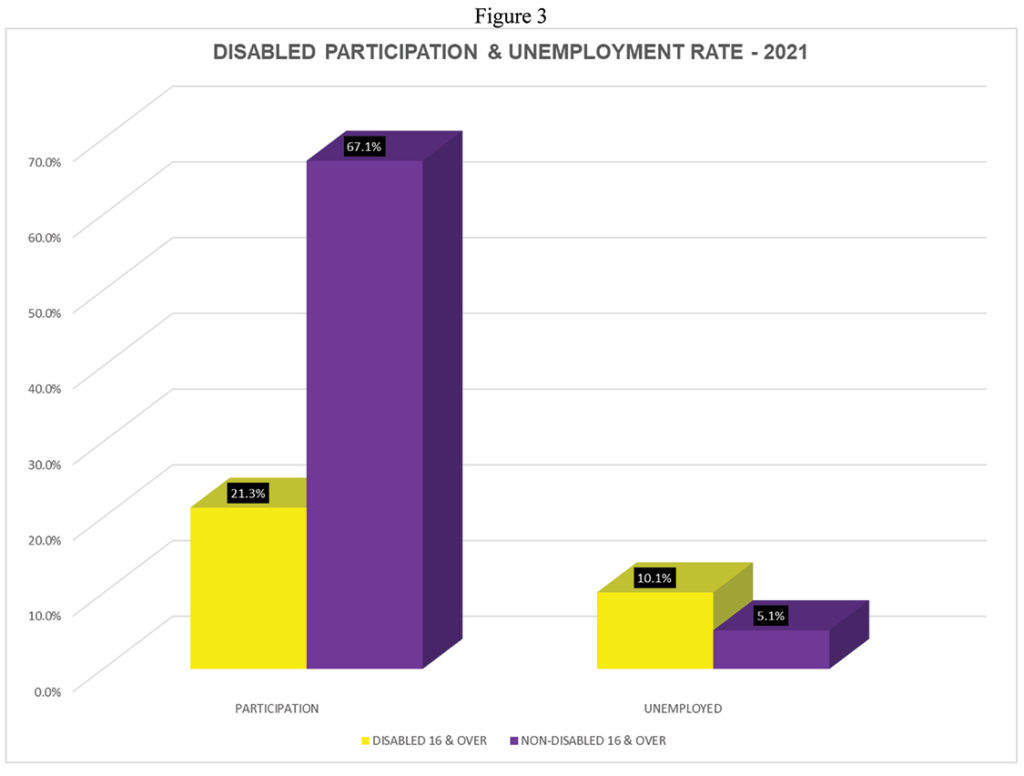

Under-utilized labor segments are another avenue to explore to attract new talent. Non-institutionalized disabled workers are a potentially valuable source of additional employees. Target Corporation has long been a leader in hiring disabled staff in both customer facing and back of house positions. As shown in Figure 3, the labor force participation rate for disabled workers is roughly one-third that of the general population and the unemployment rate for those seeking work is twice as high. Every percentage point of increase in labor force participation amongst disabled adults would result in 310,000 additional potential workers. Seniors, reinvigoration of the foreign workforce and reengagement with young workers can similarly increase options for employers. To reach under-represented segments and potential employees in general, more creative marketing and outreach approaches are needed. Casinos have very talented marketing staffs good at finding, acquiring and retaining customers. Those same skills and creativity need to be applied to hiring as well.

When it comes to reducing labor needs, automation usually comes to mind first. Automated cashiering systems, automated hotel check-in, automated retail cashiering and even automated food and beverage ordering have already moved from the realm of demonstration projects to workable everyday solutions. However, careful reexamination of operating procedures and hours of operation can go a long way toward reducing labor needs, even without any automated systems. When considering changes to service standards and operating procedures, the focus should first be on the most labor intensive or problematic hiring areas. Customer response must also be watched carefully to make sure you are not turning off valuable patrons.

The industry and the economy in general appear to be at least 18 months and potentially as much as 36 months away from achieving stabilization in the labor sector. That does not necessarily mean a return to labor force and employment levels of the last decade. However, it does mean a more stable and predictable hiring environment. While a recession would speed the return, it is a cure that is worse than the disease. It is far more preferable to have the industry make necessary adjustments, focus on the highest value customers, let lower value customers drift away if labor cannot support them and wait for the pendulum to swing back.

James M. Klas is Co-Founder and Principal of KlasRobinson Q.E.D., a national consulting firm specializing in the economic impact and feasibility of casinos, hotels and other related ancillary developments in Indian Country. He can be reached by calling (800) 475-8140 or email [email protected].