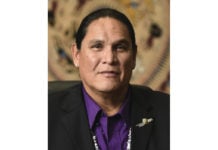

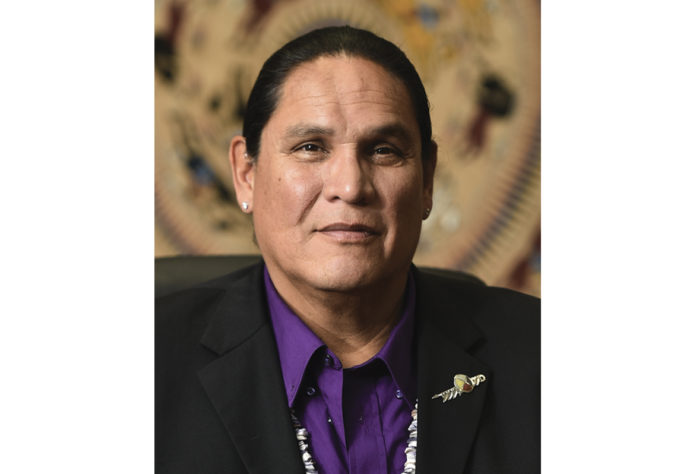

by Ernest L. Stevens, Jr.

On June 29, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, ignored two centuries of precedent by granting state courts jurisdiction over crimes committed by non-Indians in Indian Country. The decision is a unilateral unauthorized grant of power from the judicial branch to state governments over Indian lands that directly conflicts with tribal sovereignty. The case is one of an increasing list of federal court challenges to longstanding tenets of federal Indian law.

It is an undisputed fact that Native Nations pre-date the formation of the United States. Prior to contact, Indian tribes were independent, self-governing entities vested with full authority and control over their lands, citizens, and visitors to their territories. Upon its formation, the United States acknowledged the sovereign authority of Indian tribes, entering into hundreds of treaties with tribal governments to secure trade agreements, establish peace alliances, and reach promises on related governmental powers.

The U.S. Constitution acknowledges these treaties and the status of Indian tribes as distinct governments. The Constitution provides that “Congress shall have power to … regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.” This clear text establishes the framework for the federal government-to-government relationship with Indian tribes, and makes clear that Congress, not the federal courts, has exclusive authority over matters relating to Indian tribes.

For two hundred years, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld and clarified this foundational principle of Indian law: states have no power in Indian Country, absent an express act of Congress to exercise such authority.

The Supreme Court in Castro-Huerta turned this principle on its head. The Court announced a new presumption in favor of state authority, ruling that “unless [affirmatively] preempted [by an Act of Congress], States may exercise jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed by non-Indians against Indians in Indian Country.” The Court added to the damage caused by stating that the “holding is an interpretation of federal law, which applies throughout the U.S.,” essentially granting state jurisdiction in these circumstances over all of Indian Country.

In dissent, Justice Neil Gorsuch depicted the Oklahoma’s actions as an “unlawful power grab”. He added that the Court’s majority opinion was announced “as if by oracle, without any sense of the history recounted above and unattached to any colorable legal authority. Truly, a more ahistorical and mistaken statement of Indian law would be hard to fathom.”

The Oklahoma Governor led a public relations/social media campaign to tout their claims in the Castro-Huerta case, taking his false rhetoric to conservative opinion sites and cable networks. During oral arguments, Justice Gorsuch asked if the Court would “wilt today because of a social media campaign.”

The answer to this question is tragically “yes.” The Court wilted to political pressure and ignored centuries of established precedent and foundational principles of law. The Castro-Huerta decision serves only to further complicate the maze of criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. The fallout and the response from tribal leaders and our allies in Congress continues to evolve and build. However, beyond these impacts, the decision is reverberating concern with regard to related foundational principles of federal Indian law.

Anti-tribal sovereignty organizations are following the State of Oklahoma’s playbook, pairing media campaigns with increased legal attacks on federal laws designed to meet the federal government’s solemn treaty and trust obligations. These legal theories challenge the U.S. Constitution’s recognition of Indian tribes as separate and distinct sovereign governments. They falsely claim that Indian tribes are not governments but instead racial groups. The scheme is not a new legal theory, but it does represent an existential threat to tribal sovereignty.

In the fall of 2022, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Haaland v. Brackeen. The case is brought by a coalition of anti-tribal sovereignty organizations, think tanks and attorneys representing the adoption industry. They attack the Indian Child Welfare Act as unconstitutionally based on race and claim that the Act violates the Tenth Amendment anti-commandeering doctrine.

The Native American Rights Fund has characterized the case as “a coordinated, well-financed, direct attack[.] Texas and other opponents aim to simultaneously exploit Native children while undermining the law that protects them – all while potentially undermining the entire framework of federal-tribal relations. If they succeed in weakening protections for Native children it could negatively impact Native families and tribes for generations.”

Building on this growing trend, in January of 2022, Maverick Gaming, a commercial cardroom operator in the State of Washington, filed a lawsuit against the U.S. and the State of Washington, claiming that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and compacts between Washington State and tribal governments are unconstitutionally based on “race and ancestry.” The commercial cardroom is represented by the same law firm that is involved in the Brackeen case.

Like the issue presented before the Supreme Court in Castro-Huerta, the legal theories advanced by anti-tribal sovereignty opponents in the Brackeen and Maverick cases attack basic tenets of federal Indian law and policy. The commercial cardroom’s challenge to the Washington-tribal government compacts are also not new. Federal courts have previously rejected similar fringe theories. In upholding the validity of the California-tribal government gaming compacts, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reasoned that “The very nature of a tribal-state compact is political; it is an agreement between an Indian tribe, as one sovereign, and a state, as another.”

Reviewing courts also reasoned that Congress, as it debated IGRA, recognized that tribal governments had been engaged in gaming on Indian lands to generate governmental revenue long before the Supreme Court’s 1987 Cabazon decision. Congress, through IGRA, established the tribal-state compacting process to balance competing interests of the tribes and the states, which it acknowledged as “two equal sovereigns.”

The Maverick case remains at the federal district court level. While not grounded in law or fact, we take these challenges seriously, because of what is at stake. For most of the past half century, more than 240 tribal governments nationwide have utilized Indian gaming to generate governmental revenue to rebuild Native communities.

The Indian gaming industry generates more than 300,000 direct jobs on Indian lands annually. Tribal government-run gaming operations serve as economic anchors for community development and entrepreneurship. Indian gaming revenues have been used to put a new face on Native communities – rebuilding basic infrastructure, and enhancing the delivery of health, education, and public safety services to tribal government

citizens.

These legal challenges that attempt to blur the distinction between Indian tribes as a race of people as opposed to constitutionally acknowledged sovereigns are attacks on the very existence of tribal governments.

As Justice Blackmun wrote in the historic Mancari decision in 1974, if these legal challenges are upheld, “an entire Title of the United States Code would be effectively erased and the solemn commitment of the government toward the Indians would be jeopardized.”

All of Indian Country is united in denouncing these lawsuits as dangerous, destructive, and lacking any legal merit. Tribal governments are likewise united to fiercely oppose any attempt to undermine the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and the very foundations of federal Indian law and policy.

Ernest L. Stevens, Jr. is Chairman of the Indian Gaming Association. He can be reached by calling (202) 546-7711 or visit www.indiangaming.org.