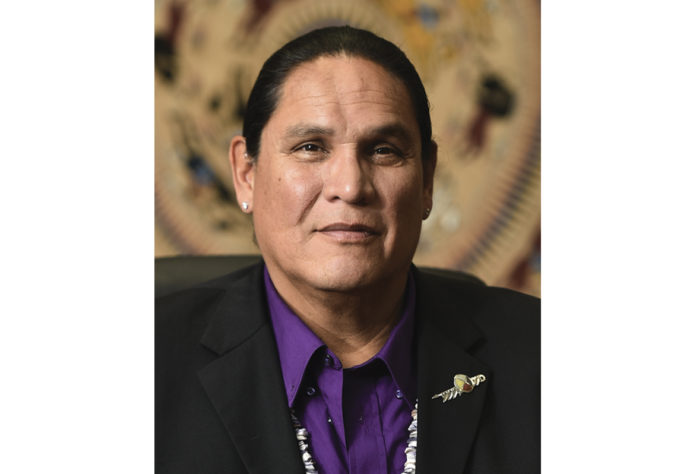

By Ernest L. Stevens, Jr.

The Native Nations settlers encountered when they “discovered” America were established long before the founding of this country. Upon its creation in 1797, the United States Constitution acknowledged this pre-existing relationship and declared that Indian tribes are separate distinct governments, Indians were citizens of these governments, and that treaties – including those entered into between the U.S. and tribal governments – are the supreme law of the land; and that state governments cannot enter into treaties with other governments.

Despite this clear expression of Indian tribes and Indian citizens as separate political entities, anti-tribal sovereignty groups are increasingly challenging federal laws designed to meet the government’s obligations to Indian Country as being race-based in violation of equal protection. These claims ignore the text of the U.S. Constitution and well-settled case law.

The most high-profile of these cases are Haaland v. Brackeen, which involved the Indian Child Welfare Act, and the Maverick Gaming and West Flagler cases challenging the validity of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

Similar questions were raised nearly a half century ago in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Morton v. Mancari decision. Mancari held that federal laws relating to Indian tribes are based upon a political or governmental classification – not racial classifications. Thus, such laws are subject to “rational basis” as opposed to “strict” scrutiny.

Mancari reasoned that a federal Indian affairs-related law “will not be disturbed” in the face of an equal protection challenge, “As long as the special treatment can be tied rationally to the fulfillment of Congress’ unique obligation toward the Indians.” Period. “End of story.”

Over the past five decades, the Supreme Court and dozens of lower federal courts have consistently upheld the model of the Mancari decision when examining challenges to the constitutionality of federal laws designed to impact Indian tribes.

Despite the well-settled precedent, the renewed interest in claiming that federal Indian affairs laws are race-based are emboldened by the Court’s recent trend of ignoring or overruling its own longstanding decisions. The Court’s June 2022 decision Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta is one example in which it ignored two centuries of precedent, turning on its head the foundational principle that state laws have no effect on Indian lands, unless expressly authorized by an Act of Congress.

In the recent cases challenging ICWA and IGRA, the anti-tribal government challengers discount and urge the courts to ignore the Supreme Court’s Mancari decision and the model that it established regarding statutory review of laws relating to Indian tribes. In addition to attacking ICWA as race-based, the plaintiffs argued that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to enact ICWA and that the law violated the anti-commandeering doctrine.

On June 15, 2023, the Supreme Court – in Haaland v. Brackeen – rejected most of these dubious legal theories. In a resounding 7-2 decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of ICWA. Instead of seeking to set new policy from the bench or ignore prior decisions, the Court returned to its foundations of statutory interpretation of federal Indian laws.

The majority opinion, authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, rejected arguments that questioned Congress’ Article I power to enact ICWA. The Court cited longstanding precedent of Congress’ “well established and broad” constitutional authority to legislate with respect to Indian affairs. The Court wrote, “We held more than a century ago that ‘commerce with the Indian tribes means commerce with the individuals composing those tribes.’ So that argument is a dead end.”

The Court also rejected, out of hand, challenges that ICWA violated the anti-commandeering doctrine, which protects state rights. Noting that it already found ICWA to be enacted pursuant to Congress’ Indian commerce authority, the Court held that “[W]hen Congress enacts a valid statute pursuant to its Article I powers, ‘state law is naturally preempted to the extent of any conflict with a federal statute.’ End of story.”

In a separate concurring opinion, Justice Neal Gorsuch – arguably the biggest champion of tribal sovereignty on the Court – detailed the tragic history that led to ICWA’s enactment, including forcing Native children into federal boarding schools. Gorsuch lauded the opinion as “further steps in the right direction,” expressing his hope that the court would “follow the implications of today’s decision where they lead and return us to the original bargain struck in the Constitution – and, with it, the respect for Indian sovereignty it entails.”

The decision, however, did not decide the question of whether ICWA violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause on the merits. The Court rejected the petitioner’s argument on grounds that they did not have standing to raise the claim. As a result, the equal protection question remains open to a future legal challenge, one which Justice Brett Kavanaugh characterized as a “serious” and “significant question under bedrock equal protection principles.” As a result, the equal protection claim remains a threat.

The law firm representing the parents in the Brackeen case are the same legal minds behind the attacks on tribal sovereignty in the Maverick Gaming case. This is no coincidence. This is no ordinary law firm that represents mom and pop shops. They don’t specialize in child custody disputes. The firm took the Brackeen case pro bono – not to serve the best interests of a child, but to lay groundwork for their attack in Maverick as part of a longstanding and coordinated attempt to undermine tribal sovereignty.

As the Native American Rights Fund stated, “This was never a case about children. The opposition was essentially trying to weaken tribes by putting their children in the middle, which is a standard tactic for entities that are seeking to destroy tribes.”

These attacks are decades in the making. One of the attorneys representing Brackeen and Maverick filed a lawsuit to overturn California’s Prop 5 in 1998, when California voters approved a statute initiative to enact tribal-state gaming compacts. He was also the Justice Department’s Solicitor General from 2001-2004, during a time when DOJ filed lawsuits and developed draft legislation to amend IGRA to limit the ability of tribal governments to utilize Class II gaming.

These cases are not only about ICWA and IGRA, they are also about tribal government culture and religion (NAGPRA), Indian water rights and legislative settlements, Indian lands (the Indian Reorganization Act and many others), Indian health care and education (IHCIA and ISDEAA), Indian housing (NAHASDA), and much more.

As Justice Harry Blackmun, a President Nixon nominee, stated in Mancari: “If these laws, derived from historical relationships and explicitly designed to help only Indians, were deemed invidious racial discrimination, an entire Title of the United States Code (25 U. S. C.) would be effectively erased and the solemn commitment of the government toward the Indians would be jeopardized.”

Opponents of Indian Country pin their hopes on the Court reverting to making federal Indian policy from the bench as it did last year in Castro-Huerta. They will ask the Court to dismiss the half century of Mancari’s precedent and reinterpret the Constitution’s clear expression of Indian tribes as self-governing entities. Essentially, they will ask the Court “to say that the Constitution itself is racially discriminatory,” as Professor Matthew Fletcher recently wrote.

If, however, the Court follows the roadmap laid out in the recent Brackeen decision, using historical rules of statutory construction and interpretation for Acts of Congress relating to Indians and Indian tribes, these legally dubious attacks on tribal sovereignty will die a quick death.

Ernest L. Stevens, Jr. is Chairman of the Indian Gaming Association. He can be reached by calling (202) 546-7711 or visit www.indiangaming.org.