SEATTLE, WA – The King County Council voted unanimously in favor of a landmark settlement with the Suquamish Tribe to redress the repeated release of sewage into Puget Sound from the county’s wastewater collection and treatment system.

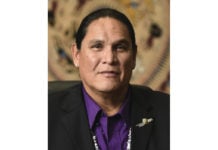

“The Suquamish Tribe is pleased that King County recognizes the seriousness of this issue and worked with us to protect Puget Sound,” said Suquamish Tribal Chairman Leonard Forsman.

The settlement is designed to curtail further wastewater pollution of Puget Sound from King County facilities, including the West Point Wastewater Treatment Plant (WPTP). The settlement also funds ecological restoration projects in Puget Sound that will support the recovery of salmon, orca, and other marine life, and it compensates the tribe for past releases that continue to impact tribal fisheries.

Settlement talks began following a July 2020 notice from the Suquamish Tribe that it intended to file a lawsuit for violations of federal clean water law and for infringement on the tribe’s treaty rights.

“In 2019, tribal canoe families from all over the Salish Sea landing in Suquamish during the annual Tribal Canoe Journey had to paddle through one of the county’s largest untreated sewage spills,” said Forsman. “This pollution, created an immediate health hazard for the tribal community and disrupted an important cultural event.”

“The tribe took legal action when it became clear that the county was failing to protect the water quality in Puget Sound as required by the Clean Water Act, and the pollution was interfering with our treaty fishing rights,” said Forsman. “We could no longer stand on the sidelines hoping conditions would improve.”

The 2019 event was just the latest in a series of pollution events. In July 2020, the tribe notified King County that it was responsible for at least 11 significant illegal discharges of untreated sewage from the WPTP into the tribe’s treaty-protected fishing areas, with individual discharge events ranging from 50,000 gallons to 2.1 million gallons. The tribe further notified King County officials of the tribe’s intent to file a lawsuit for ongoing violations of the Clean Water Act and its National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit.

Unlawful discharges of sewage foul the water and habitat for aquatic species, result in closure of beaches where Suquamish tribal members harvest shellfish, prompt recalls of commercially sold shellfish, interfere with tribal member harvest and sale of salmon, and disturb important cultural activities such as the annual Canoe Journey. Fecal coliform bacteria pollution is a persistent threat to human health, and the safe harvest and consumption of fish. The discharges also foul beaches and waterways enjoyed by non-Native residents of King County, Bainbridge Island, Kitsap County and throughout the Puget Sound.

One of the purposes of the Clean Water Act is to eliminate untreated sewage discharges such as those that have been occurring regularly in Puget Sound and to protect the health of all citizens.

Sewage pollution from King County’s outdated wastewater treatment processes are not new. In 2013, King County entered a consent decree with the State of Washington and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address serious and ongoing sewage discharges from the county’s wastewater treatment facilities and combined sewer outfalls. In spite of the consent decree and a series of enforcement actions against King County, Clean Water Act violations continued, including major releases from WPTP that repeatedly impacted the tribe’s treaty-reserved fishing rights and cultural activities.

The county acknowledges in the settlement that sewage spill events from its wastewater collection and treatment system into the tribe’s treaty-protected fishing area have impacted the tribe’s right to take fish and tribal cultural events, and that this pollution has the potential to impact the tribe’s treaty rights in the future. However, the county does not admit to liability for any alleged violations.

The settlement agreement requires the county to upgrade infrastructure to eliminate or reduce further untreated discharges from King County wastewater and sewage facilities into Puget Sound. The agreement also requires compensation to the Suquamish Tribe to cover legal and technical costs associated with the discharges, and to compensate for damages. The settlement also requires the county to invest in environmental projects that will make up for the damage to marine habitats caused by the spills.

To address tribal impacts, the county agrees to pay the Suquamish Tribe $2.5 million to compensate for impacts to the tribe associated with the last five years of discharges and future tribal impacts from any additional spills that might occur through the end of 2024. After January 1, 2025, if any sewage is discharged from WPTP’s emergency bypass, the county will will pay a penalty to the tribal mitigation fund for each spill event.

To reduce or eliminate future untreated sewage spills, particularly at WPTP’s emergency bypass, King County agrees to substantial infrastructure upgrades at WPTP. The upgrades include replacing faulty uninterruptible power supply, addressing voltage sag, and creating redundant capacity to deal with peak flows. A strict and enforceable penalty framework is tied to the infrastructure upgrade deadlines, and if missed, the county is required to pay $40,000 for a missed deadline and $10,000 for each additional month of delay.

“This framework holds the county accountable for protecting the water quality in Puget Sound,” said Chairman Forsman.

The county will complete supplemental environmental projects tied to near-shore habitat restoration or other mutually agreed environmental protection projects in the amount of $2.4 million within five years.

“The tribe is pleased that the county negotiated in good faith to protect our shared waters,” said Forsman. “This settlement will result in significant steps towards protecting the marine life of Puget Sound. The entire Puget Sound community deserves clean water. The shellfish, orca, salmon, crab, geoduck and shrimp all rely on a healthy marine environment, and all of our children – and children’s children – deserve clean water.”