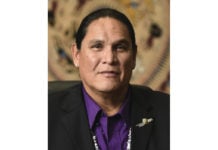

by Hilary C. Tompkins

The summer got off to a busy start for developments in Indian gaming law, with notable decisions in June from coast to coast at both the state and federal levels.

In Washington State, the Spokane Tribe successfully defended its casino’s approval before a federal circuit court. In Connecticut, MGM handed a victory to the Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan Tribes when it dropped its suit against a proposed casino. In Maine, meanwhile, an effort to pave the way for the tribes to enter the gaming field was stymied by Governor Janet Mills (D). And in late June, the U.S. Supreme Court let stand the Interior Department’s approval of an off-reservation casino for the North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians in California.

The Ninth Circuit started the busy month off on June 1, ruling that the Interior Department properly approved a Spokane Tribe casino under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act’s (IGRA) off-reservation two-part determination. The nearby Kalispel Tribe had challenged the approval of the casino, which now operates near Spokane, arguing that it breached the Department’s trust duties. The Kalispel Tribe’s central claims were that the approval violated IGRA’s rule against casinos that are “detrimental to the surrounding community,” and was invalid under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The Kalispel Tribe had argued that the Spokane Tribe’s casino would cost the former tribe $30 million in its first year of operation and more thereafter.

But the Ninth Circuit agreed with the federal district court, finding that the Department reasonably concluded that even with the projected income loss, the tribe would still be able to provide services for its members. The court also ruled that the district judge correctly evaluated the Department’s assessment of the casino’s effects on a nearby Air Force base, the Department’s consultations with Spokane County, and a final environmental impact statement under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

The Ninth Circuit’s ruling further clarifies the meaning of IGRA’s two-part determination requirements. These requirements condition approval of off-reservation gaming on the Interior Secretary’s determination that the project is (1) within the best interests of the tribe and its members; and (2) will not be detrimental to the surrounding community. According to a lawyer for the Spokane Tribe, the decision aligns the D.C. Circuit and the Ninth Circuit in finding that if a nearby tribe suffers a loss, a court should evaluate whether a project is “detrimental” by reviewing its overall effects on the community, not on any single member of that community.

Meanwhile, in mid-June, MGM Resorts dropped its lawsuit against the Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan Tribes’ planned casino in East Windsor, CT. The proposed site was just 12 miles from MGM’s Springfield, MA location. MGM had argued that the Interior Department’s approval of re-negotiated gaming agreements between Connecticut and the tribes was unfair and violated IGRA and the APA.

But MGM’s litigation became unnecessary due to a new gaming expansion compact agreement between Connecticut and the tribes negotiated earlier this year that shelved the East Windsor project. Governor Ned Lamont (D) signed the agreement into law in May, and it will require the Interior Department’s approval. The new state law permits the tribes and the state lottery to provide sports betting, and the tribes may also provide online casino gaming. It also halted the East Windsor project for at least a decade. As a result of this new arrangement, in a June filing in federal district court in Washington, D.C., MGM dismissed its lawsuit, retaining the option to refile it.

Further north in Maine, the state legislature passed a law permitting tribal gaming under IGRA, but Governor Mills vetoed the measure. Passage of the law was a temporary victory for the Maine tribes in their decades-long effort to join other tribes nationwide in the gaming field. A federal court had previously ruled that Maine’s Indian Claims Settlement Act preempted IGRA and that IGRA therefore didn’t apply in Maine or to Maine tribes. The new law would have amended the Settlement Act to permit tribal gaming to move forward.

Unfortunately, Governor Mills vetoed the measure and, as of press time, it was not clear that a legislative override would occur. Reasons provided in the Governor’s veto include: (1) the legal question of whether a state law permitting gaming under IGRA is effective without a corresponding amendment to the federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act; (2) concern that the legislation lacked specificity regarding where tribal gaming could occur and the scope of gaming; (3) increasing competition for the two existing gaming facilities in the state; (4) the application of tribal laws in lieu of state laws regarding health and safety; and (5) concern that the tribes would only engage in Class II gaming that is not subject to the IGRA compacting process, drawing business away from existing gaming operations, and depleting state gaming tax revenue. The Governor expressed her view that the tribes have been unfairly excluded from gaming in the state and pledged to continue working with them on a solution, but concluded this new legislation was not the right approach.

On a more positive front, the U.S. Supreme Court left standing the Interior Department’s approval of an off-reservation tribal casino in California. The proposed casino would sit on land that the Department took into trust for the North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians. Two nearby card rooms, Club One Casino and GLCR, sued the Department, contending that the Department’s approval violated IGRA because the North Fork tribe purportedly lacked sufficient ties to the land and the land actually remained under state jurisdiction.

But a federal district court disagreed, ruling in 2018 that the land was under tribal jurisdiction by virtue of the government’s having taken it into trust. The court also found that the approval followed all required procedures. The Ninth Circuit affirmed those rulings in May 2020. On June 21, the Supreme Court turned away the card rooms’ appeal, leaving the decisions below intact.

The summer’s developments so far show that strong tailwinds are pushing Indian gaming forward even in the face of opposition from other tribes or gaming enterprises, but that having state and federal allies is vital. The reality is opposition to Indian gaming remains consistent and vigorous and continues to raise the cost of any effort to launch new Indian gaming ventures, particularly on recently-acquired trust lands or off-reservation. These legal developments also reflect the importance of having a strong Interior Department record to support gaming approvals and the benefit of developing negotiated solutions with state officials, when feasible.

Hilary C. Tompkins (Navajo Nation) is former Solicitor of the U.S. Department of the Interior (2009-2017) and is currently a partner at Hogan Lovells in Washington, D.C. She can be reached by calling (202) 664-7831 or email [email protected].