by Sam Cohen

As pre-pandemic life increasingly returns, we need to return to tribal tax reform and parity issues such as the draconian limitation on tribes to only issue tax exempt bonds for essential government functions. Since 2009, dozens of tribes have successfully side-stepped the essential government function (EGF) limitation by issuing Tribal Tax-Exempt Development Bonds (TEDBs). But as of February 1, 2022, the amount of remaining available national volume cap is $62,942,285. Congress needs to either eliminate the EGF or reauthorize and replenish the TEDB program.

The Draconian Essential Government Function Test

The Essential Government Function test in Section 7871 of the Internal Revenue Code essentially blocked any meaningful tax-exempt financing in Indian Country. However, with the enactment of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), Congress authorized the use of Tax Exempt Development Bonds (TEDBs), a pilot program which has since demonstrated the need to eliminate the EGF. Specifically, Section 1402 of Title I of Division B of the ARRA, Pub. L. No. 111-5, 123 Stat. 115 (2009) (the “Act”), added new § 7871(f) to the Code. The purpose of new § 7871(f) is to give Indian tribal governments greater flexibility to use tax-exempt bonds to finance economic development projects than is allowable under the existing standard of § 7871(c). The more restrictive standard under § 7871(c) generally limits the use by Indian tribal governments of tax-exempt bonds to the financing of certain activities that constitute essential governmental functions customarily performed by state and local governments with general taxing powers and certain manufacturing facilities. The more flexible standard under new § 7871(f) generally allows Indian tribal governments to use tax-exempt bonds under the new $2 billion volume cap to finance any economic development projects (excluding certain gaming facilities and projects located outside of Indian reservations as provided in § 7871(f)(3)(B)) or other activities for which state or local governments could use tax-exempt bonds under § 103.

The ARRA also created a safe harbor for projects that did not share common walls, roof or floor with the gaming facility. (Notice 2009-51), thus allowing tribes to finance projects adjacent to gaming facilities, but not the gaming facilities themselves. Even with this safe harbor, initial allocations of TEDBs were slow due to a reluctance from the lending community. In fact, only 3% of the TEDBs $2 billion was allocated in the first two tranches in 2010 and 2011.

The Chumash Experience

In 2011, Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and the Chumash Casino Resort received an allocation in the second tranche of TEDB funding from Treasury, but because the tribe did not yet have the land on which the improvements were to be made in trust, Treasury refused to enter into the loan agreements. Finally, in 2014, Chumash was able to revisit the TEDB program, securing a TEDB allocation of $86,430,000, enough to finance a new hotel tower and parking structure. However, of that amount, Chumash was able to only draw down $100,000 before having to forfeit the balance as construction was not complete within 180 days, as mandated by Treasury. Fortunately, Chumash received a second allocation in 2016 to complete the project. Later, draw down rules were added by Revenue Notice 2015-83 for TEDB programs to reflect the realities of construction draws and eliminating the 180-day completion requirement.

While $86,430,000 is a good deal of money, the size of our project was relatively small in the world of corporate finance and the Chumash bonds were secured under a five-year bank note rather than a traditional bond offering. While choosing this path carried fewer administrative burdens, it also meant the bonds would need to be refinanced before the note would be fully repaid. Just as Treasury failed to contemplate the actual time it might take to complete construction on a project, they also failed to recognize TEDBs might need to be refunded (refinanced). After three years of meetings, and a nearly depleted TEDB account, Treasury finally issued IRS Notice 2019-39, which stipulates that tribes are able to refund their outstanding TEDBs without the need to secure additional volume allocation.

TEDBs Benefit More Than Just Tribes: The Chumash Casino Resort TEDBs

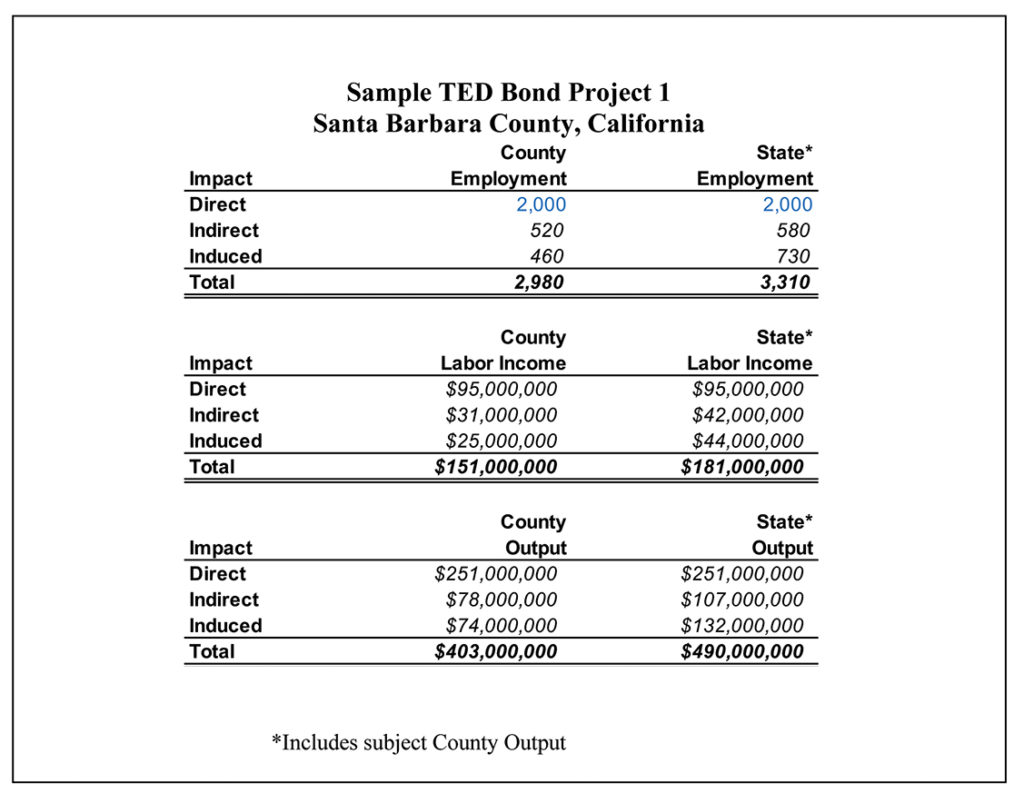

As noted above, the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and its Chumash Casino Resort issued $86,430,000 of TEDBs as part of its $171-million tribal hotel, conference center, parking garage and museum construction in Santa Barbara County, California – completed in May 2016 with a stabilized direct employment of 2,000.

Estimates of indirect and induced impact were prepared by KlasRobinson Q.E.D. using the Impact Analysis for Planning (IMPLAN) economic model developed in 1979 at the University of Minnesota and maintained by IMPLAN Huntersville, NC. The IMPLAN model accounts closely follow the accounting conventions used in the “Input-Output Study of the U.S. Economy” by the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the rectangular format recommended by the United Nations.

Induced impact calculated by the IMPLAN model reflects changes in spending from households as income/population increases or decreases due to changes in production, effectively measuring the impact of wages paid as they cycle through the economy. Indirect impact calculated by the IMPLAN model reflects changes in inter-industry purchase, effectively measuring the impact of expenditures for other goods and services by the tribal enterprises as they too cycle through the economy.

Based on those estimates of employment generated by the new or expanded enterprises, three levels of regional economic benefits have been calculated: annual output – equivalent to GDP, employment, and earnings – equivalent to personal income.

Conclusion: Tribes Should Have the Same Abilities to Finance Hotels, Parking Lots and Convention Centers as States with Tax-Exempt Bonds

In responding to the 2006 GAO Report to the Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate (09-13-2006), then Senator Max Baucus commented:

“This report illustrates the benefits that state and local government enjoy because of the flexibility that they have in their use of tax-exempt bonds. Tribal governments shouldn’t have to climb higher mountains just to use tax-exempt bond funds. Tribes deserve the same flexibility to use tax-exempt bond funds that state and local governments have. (Press release dated October 13, 2006).”

The Supreme Court’s view of economic development as an essential governmental functions bears repeating:

“Promoting economic development is a traditional and long accepted governmental function, and there is no principled way of distinguishing it from the other public purposes the Court has recognized.,Kelo v. City of New London, 125 S.Ct. 2655 (2005).”

It is difficult for tribes to get credit to begin with. The Essential Government Function test has effectively blocked any meaningful tax-exempt financing until the ARRA authorized the TEDBs in 2009. Even with TEDBs, there were difficult procedural rules that delayed the program for almost ten years. However, it is now clear that this pilot project has been a success and most (but not all) of the bugs have been worked out of the initial program.

How Can You Help?

In a perfect world, Congress would repeal the Essential Government Function limitation on tribal tax-exempt bonds. Such a provision was inserted in the Build Back Better proposed legislation recently considered by Congress. While it is unlikely that bill will become law, efforts remain within Congress to adopt portions of that legislation, including the elimination of the EGF. Tribes and those working with tribes in the financial community should ask members of Congress to

eliminate the EGF whenever possible.

Second, while not a permanent fix, tribes can encourage Congress to reauthorize the TEDB program by increasing the volume cap that was created in the 2009 ARRA and is now almost fully allocated. Even if a stand-alone bill is not possible, Congress should consider another ten (10) year program of TEDBs that might be considered under budget reconciliation or as part of an extenders package.

Third, please share your TEDB success stories. We need to document the economic benefits of TEDB financed projects both for each tribe and the areas surrounding each tribe.

Sam Cohen is Government Affairs and Legal Officer for the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. He can be reached by calling (805) 688-7997 or email scohen@santaynezchumash.org.