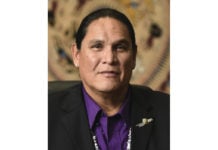

by Jonodev Chaudhuri

Many recent developments indicate that Indian gaming may have just reached an evolutionary milestone. We’ve come quite a long ways since the Supreme Court upheld the inherent right of tribal nations to regulate gaming – to the exclusion of states – on tribal lands in Cabazon. This past June, the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC) announced a record $41.9 billion in gross gaming revenue for the year of 2023, and with the Supreme Court’s denial of the cert petition filed in West Flagler Associates v. Haaland, federal courts have officially accepted a compact negotiated by a state and tribe that allows the tribe to engage in and regulate sports betting with customers located off of Indian lands, using the spoke and hub model with servers located on the tribe’s Indian lands.

These are incredible developments – developments that could open the door for more innovation and entrepreneurship, which could bring even greater revenues to tribes seeking to fund their governments, services, and programs that preserve their culture and traditional ways. After all, that is why tribal nations sought to engage in gaming in the first place. Gaming has always been a mechanism to preserve and protect the inherent sovereignty of our nations, as well as the unique cultures and lifeways of our Native peoples.

It is therefore critical that, while we stand at this juncture between Indian gaming of the past and Indian gaming of the future, we make conscientious decisions, collectively, about the direction in which we want Indian gaming to go. The transformations about to unfold have the potential to significantly expand the footprint of Indian gaming. They also have the potential to hand the keys over to third parties and entities that do not have Indian Country’s best interest at heart.

For instance, following the denial of the cert petition in West Flagler Associates, companies are now scrambling to put together bids and proposals to secure contracts to license sports betting to tribes around the country. While offering and regulating sports betting could potentially be advantageous to any tribal gaming enterprise, how tribes go about engaging with vendors is of critical importance. Some companies offer sports betting contracts in a fashion where they license their brand to the tribe, at a steep price, but provide no other real services to the tribe. As tribes explore various models to amend and modify their compacts with states such that they can engage in and regulate sports betting, it is critical that tribes remain mindful of who benefits from the contracts tribes sign, and ultimately, ask ourselves just what a particular vendor is offering and whether they are offering enough. Questions to consider before contracting with any particular vendor include: What will this vendor do with player data? How will this vendor assist the tribe in building upon existing retail branding and player bases? Will this vendor provide fair-value rates for actual services? Will the vendor enhance the marketing of tribally developed branding? While it is certainly reasonable for tribes to partner with vendors for their unique expertise, tribes should not undervalue their player data that they have for years developed. If greater market access is truly being provided by a vendor, the actual benefit to the tribe should be quantified and valued accordingly. Tribal nations may not have wielded significant power and leverage in 1988, but it is 2024, and our leverage in the larger gaming industry has grown significantly.

At the same time, we must also remember that the benefits of Indian gaming have been uneven throughout Indian Country. While some tribes have benefited significantly from Indian gaming, not all tribes have benefited equally. As we sit at this crossroads, we must ask ourselves, will the advent of sports betting and other innovations in Indian gaming benefit the have-nots or the have-everythings?

In many states, the tribes that will be able to offer sports betting will be the first to market, leaving little to no room for those who follow thereafter. In negotiating compacts to allow for sports betting, some states will try to pit tribes against one another. This will look very different in a state like Florida, that has only two tribal nations, as opposed to a state like California, that has over a hundred. In states where the first tribe to market with sports betting will capture the majority of the market, many tribes will inevitably be left behind. Given the inequities that already exist in gaming revenues and market shares from tribe to tribe, we must ask ourselves whether we are comfortable with allowing the advent of sports betting to further entrench these inequities – or, whether we wish to use this opportunity to equal the playing field and move forward collectively, in a way that benefits all of our sister tribal nations.

At the end of the day, the goal of Indian gaming was, at the outset, to preserve and protect the inherent sovereignty of our nations, as well as our culture. As Indian gaming continues to evolve, and as our tribal nations and tribal gaming enterprises gain more sophistication, capital, power, and influence, we must take a moment to check whether we have maintained a commitment to the original purpose of Indian gaming. Recently, there have been instances where profits and revenues gleaned from gaming have been prioritized over preserving our Native cultures and lifeways. Sacred sites and burial grounds have been pulverized to build a casino.

But it does not have to be that way. In Indian Country, we do not have to sacrifice who we are as Native people; we do not have to sacrifice our culture and traditional lifeways just to have economic development. And we do not have to take advantage of, or try to out-maneuver, our sister tribal nations just so we can have a seat at the Indian gaming table. We have the intelligence, experience, and teachings necessary to collaborate in a way that advances Indian gaming significantly, while also ensuring that our advancements do not entrench decades-old inequities across Indian Country.

And, as a reminder, technological offerings provide additional options to tribes. Some of the age-old concerns for tribal operators should continue to be kept in mind. At NIGC, I felt it important to prioritize the agency’s responsibility to assist tribal operators and regulators in their efforts to protect against third-party bad actors. We called that initiative “Protecting Against Gamesmanship.” Tribes have much more in-house expertise than they did in 1988, and the need to outsource expertise is surely less than it was 36 years ago. That said, tribes still regularly work with vendors and consultants in their operations. IGRA’s sole proprietary interest, management without an approved contract, and appropriate use of net revenue provisions must continue to inform any engagements with third parties. Outside expertise may be helpful, but once such expertise bleeds into diluting the primary beneficiary status of tribal nations in their operations, such engagements diminish tribal power and violate the foundational principle behind Congress’s passage of IGRA.

In my time at NIGC and beyond, I have been regularly asked to mitigate challenges created by advisors who either did not have a tribe’s best interest at heart, or perhaps benignly convinced tribes to take on unduly risky behavior. While entrepreneurship necessarily requires risks, tribes should be wary of any advice that they cannot confirm is sound and that exposes a tribe to greater risk than the person providing it.

As we think about the future, some guideposts might be helpful. As tribes adopt technologies in the areas of AI, large-scale data analytics, behavioral psychology, and targeted marketing, tribes should seek to use their collective power to maximize collective or individual tribal ownership of such technologies, collective or individual control over such technologies, and collective or individual benefit from such technologies. In other words, partnering with third parties certainly can and has produced win-win outcomes. But with Indian Country’s increasing muscle, we must look to ascertain what Indian Country can do to ensure that any player knowledge gleaned from our operations is utilized to enhance other areas of tribal economic development. And, we must consider what Indian Country can do to ensure that the increased financial and economic muscle that is gained from these platforms is used to leverage other cultural and governmental priorities of Indian Country. A good case in point is the ongoing Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) crisis – an appropriately high profile issue in Indian Country. When it comes down to it, one of the primary challenges in that issue involves holding federal and state governments accountable when they fail to prioritize investigations and prosecutions of crimes against our people. The player information available in Indian gaming is massive. We should consider how we can use lessons learned from Indian gaming to both leverage our federal and state partners, but also provide greater or enhanced investigatory tools with the security apparatuses of our casinos in conjunction with those offices. It could well be that the security tools we have at our disposal could assist tribal, state, and federal law enforcement agencies in finding and locating our missing relatives.

It is truly up to us where we go from here. As tribes that are engaged in gaming continue to gain power and capital, we must keep in mind that without culture, we have no tribal sovereignty. And without tribal sovereignty, we have no Indian gaming. As we move into the future of Indian gaming, let’s not forget who we are as Indian people. Indian gaming is changing. How can we use this for the better?

Jonodev Chaudhuri is Principal at Chaudhuri Law and Ambassador of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Chaudhuri served as Chairman of the National Indian Gaming Commission from 2013-2019. He can be reached by calling (480) 216-9483 or email [email protected].